Martial law is a still-timely but little-researched topic. A justice of the United States Supreme Court predicted that the imposition of martial law would come to be regarded as one of the two most notorious acts of the U.S. government during the war, along with the mass internment of Japanese Americans. His prediction about the internment was born out, but not his prediction about martial law. On the contrary, martial law has been all but forgotten.

The limited discussion of martial law usually revolves around the blackout and rationing. The huge issues of constitutional law and human rights are largely forgotten, but a core question persists: In a climate of fear, what happens when people’s constitutional rights are suspended and unlimited power is placed in the hands of the Army?

Martial law becomes a pointedly relevant topic in the post-9/11 political and social environment. Military tribunals, selective suspension of habeas corpus and imprisonment without charges are central to the history of martial law just as they are to the questions of 9/11.

What was martial law? Was it justifiable? Did it go on too long? Once the Army gained power, how did they use it? How determinedly did they resist giving it up? In the end, was it legal or illegal? Was it a net benefit to the people of Hawaii? Or did it do damage to the values and practices of Hawaii?

Original research from varied primary sources can be readily accomplished at the University of Hawaii Hamilton Research Library and less directly through the National Archives. Comparatively small but impressive amounts of material are in the Hawaii State Archives and the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii.

University of Hawaii Hamilton Research Library

Hamilton Research Library is a largely untapped mine of material on Martial Law. For an online overview, search the web for University of Hawaii Archives and Manuscripts + Collections + Hawaii War Records Depository (HWRD)

HWRD – Established by the Hawai’i Territorial Legislature in 1943, HWRD contains a unique record of Hawaii at war. To make an appointment in the HWRD reading room e-mail archives@hawaii.edu or call (808) 956-6047. If you know from the finding aid what you want to study, the archivist may have your material waiting for you. The archivist can also help you consult the original card file. Index cards will lead you to rich files on martial law.

With the on-line Digital Collection, you can view 1,800 U.S. Signal Corps and newspaper photos. You can also find a wealth of unexplored topics in either the uncatalogued subject files or the wartime scrapbook series.

Within the archives, the Romanzo Adams Social Research Libary (RASRL) can take you into parallel and sometimes deeper material. On-line, see University Archives Collections + Schools, Colleges and Institutes + Romanzo Adams Social Research Laboratory HWRD Uncatalogued RASRL (Online) Finding Aid. From 1924 to the early 1960s this institute studied race relations in Hawaii. During the 1941-1946 period, it broadened its scope to a wide-ranging examination of a society living under the stress of world war. Under RASRL War Records Laboratory, you will find the files of civilian groups dedicated to dealing with wartime conditions, including most famously the Japanese American Emergency Service Committee. Also see Student Papers including notably Subsection J, primarily the papers and diary entries of students during wartime; also Reactions to the Bombing, which includes hundreds of entries by students.

U.S. National Archives

The search engine within the vast National Archives site is ARC (Archival Research Catalog). If you want to research the name of one of Hawaii’s nearly 1500 internees under martial law, just enter the name in the ARC search window. You then can email the archivist desk with the name and locator information. If the file is less than 20 pages long, the archivist will send you the photocopies free. For each additional page, there is a charge.

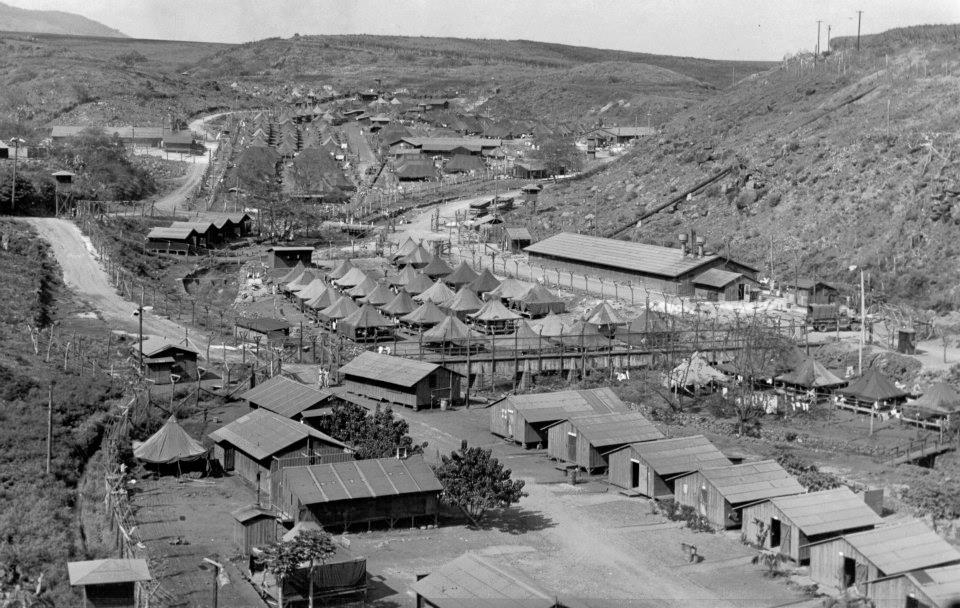

After that work gets more complicated. Archives are organized by Record Group (RG), which is then broken out by ARC identifier numbers. Home base is RG 494.3, “Records of the Military Government of Hawaii 1941-46.” An even broader category is “Records of U.S. Army Forces in the Middle Pacific (World War II), 1940 – 1959, ARC Identifier #559460. It “consists of case files, containing front and profile photographs (mug shots) of the internees, forms, fingerprints, Alien Hearing Board transcripts, reports, lists of items, and index cards. The records contain personal background information about internees such as date of birth, address, marital status, religion, occupation, medical condition, and history. Also, the records pertain to the loyalty of internees, clothing issued to internees, items confiscated from internees, suspected subversive activity, reasons for internment, and information on relocation to either the United States mainland or the country of Japan.” All of this is unrestricted.

ARC Identifier 1079759 consists of “copies of general orders pertaining to a variety of matters including: blackouts, censorship, liquor control, citizen and alien registration, structure of the military government, appointments of unit directors, the judicial system, cargo and passenger control, labor control, food control, land control, travel restrictions, internment of aliens and Japanese-Americans, restricted areas, air raids, internal security, property control, finance and personnel.”

Hawaii State Archives

A comparatively small but interesting amount of material is available in the Hawaii State Archives, located between Iolani Palace and the State Capitol. Again, consult the archivist. Ask for a Finding Aid on Ingram Stainback, the nearly powerless civilian governor during martial law. See files on martial law that include Stainback’s letters to the U.S. Interior Department complaining about the military’s hanging on to power. A second file of includes the lists of names of the many workers who were jailed and/or fined for missing work or attempting to change jobs. It is a perspective on the arbitrary power of martial law General Orders.

Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i (JCCH)

JCCH has played a significant role in reviving interest in internment in Hawaii. Compared to the western United States, where all people of Japanese ancestry were relocated, and most were interned, about 1500 people, or less than one percent of the Japanese-ancestry population, were interned in Hawaii. Quite naturally internment isolated people physically, psychologically and socially but to what extent did Martial Law also do that? To what extent was Martial Law a substitute for internment?