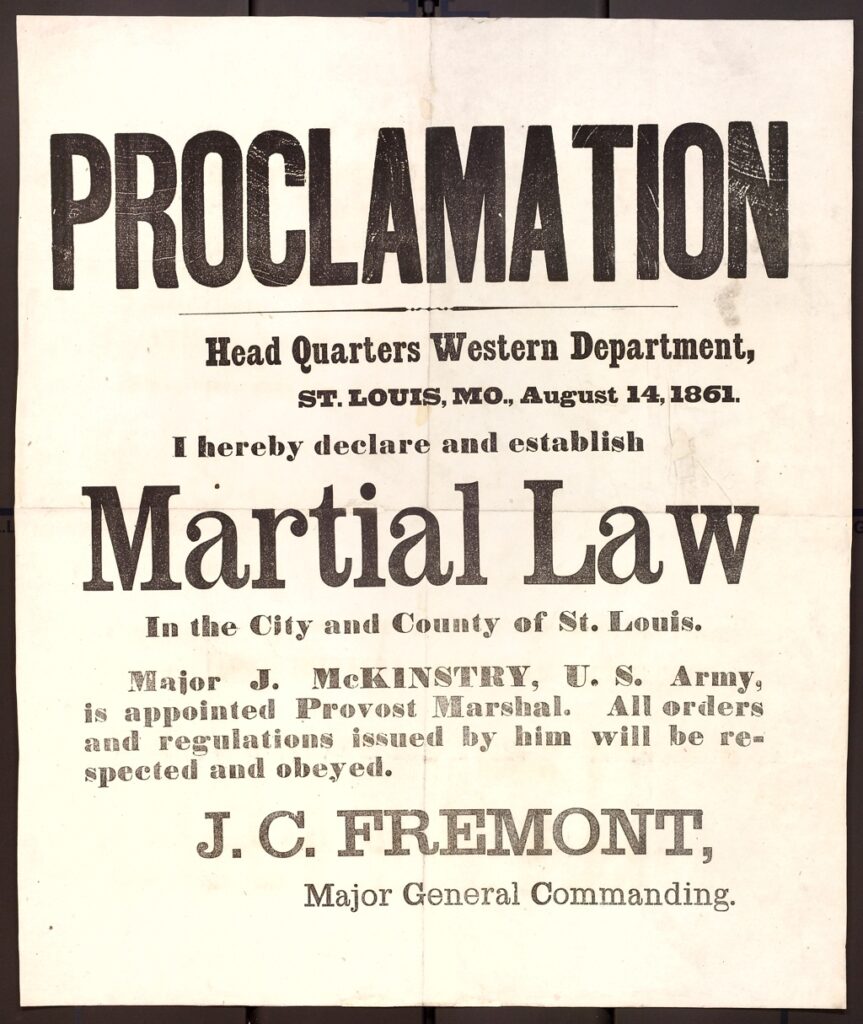

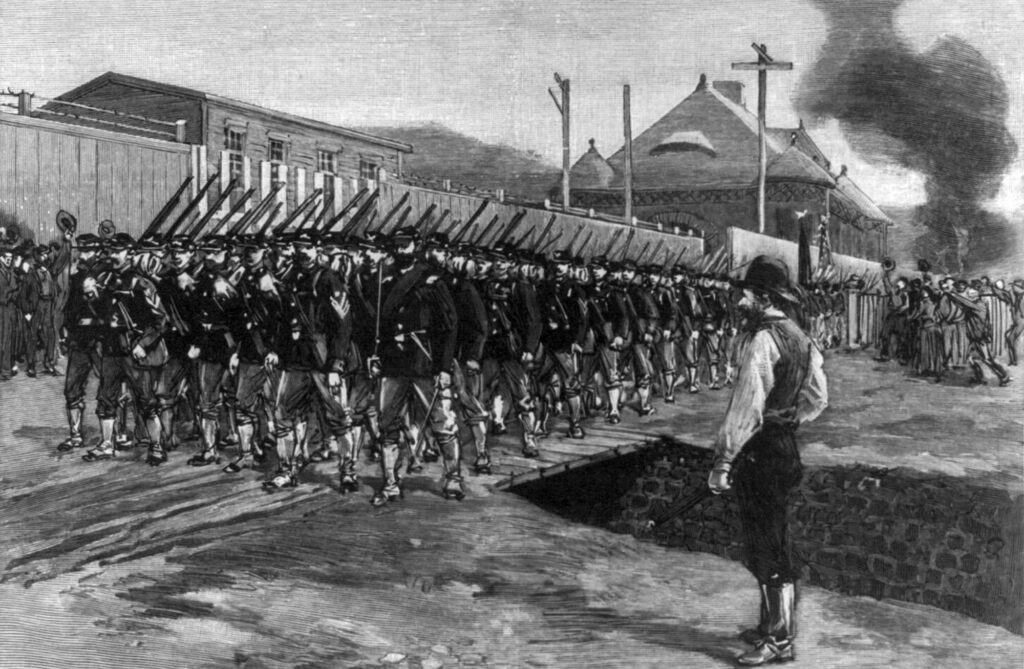

During the Civil War Congress passed several laws to deal with acts of treason and rebellion against the federal government. With several million people taking part in the “rebellion” and no federal judicial authority to deal with them, such acts were not enforceable in the South. In areas under federal control, a policy of having the military deal with persons suspected of treason and rebellion was adopted. At first, the policy applied only to particular localities, mostly in the embattled border states.

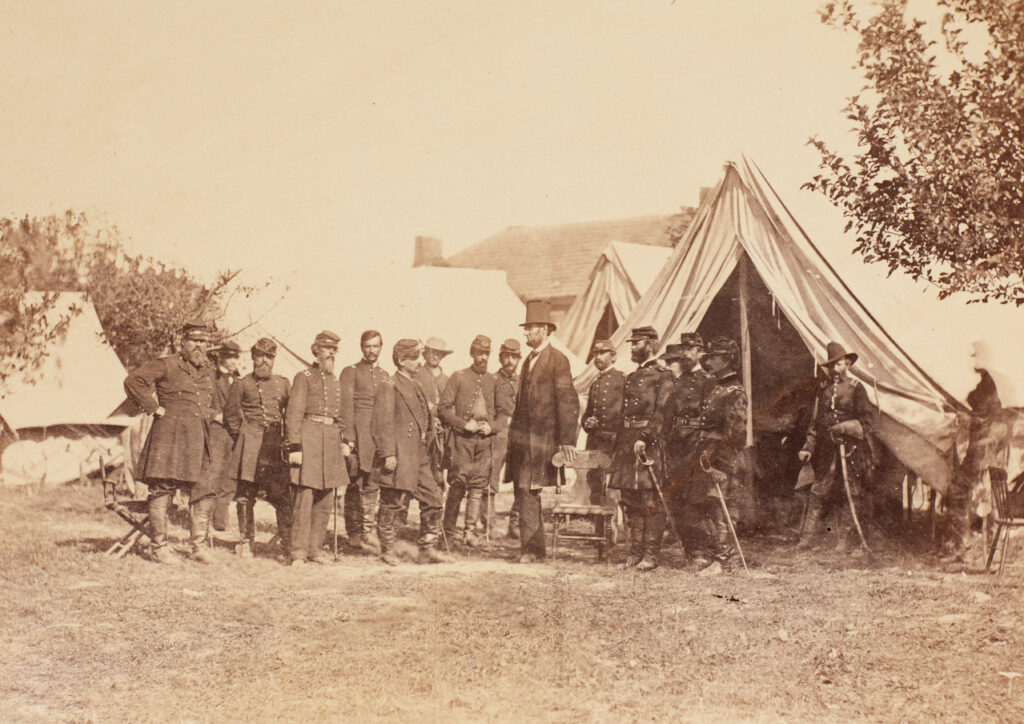

In September of 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a sweeping proclamation declaring that all persons obstructing enlistments, resisting the draft or giving aid and comfort to rebels “shall be subject to martial law, and liable to trial and punishment by court-martials or military commissions.” Habeas corpus privileges were suspended for all persons arrested or already imprisoned on such charges. Approximately 18,000 civilian suspects were rounded up and held until their potential threat to the Union cause could be assessed. Most were released within a few days after taking an oath to refrain from secessionist activities.

Suspension of such a fundamental civil liberty as habeas corpus roused sharp protests. The habeas corpus right developed in Anglo-American law to prevent the government from arbitrarily arresting and holding individuals without charging them with a crime (an ideal way of suppressing political opposition). The right was compromised during the Civil War, however, because suspects could escape to rebel areas if they were not held by military authorities.

This issue resulted in a confrontation between the President and the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. On circuit in Baltimore, Chief Justice Roger Taney issued a writ of habeas corpus for a Maryland secessionist charged with destroying railroad bridges. When union officers ignored the writ, Taney issued an opinion in Ex parte Merryman (1861) denying the president the power to suspend the writ because the section on habeas corpus and its suspension was in Article I, section 9 of the United States Constitution, which dealt with the legislative power of Congress. Lincoln’s reply to Congress stated that breaking the law “to a very limited extent” was preferable to having government handcuffed and unable to suppress the rebellion.

In March 1863, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Act, which “legitimized” the president’s internal security program without jeopardizing its authority or that of the federal judiciary. The statute authorized the president to suspend the habeas corpus privilege but required the government to provide federal courts with lists of political prisoners being held and to release those whom grand juries failed to indict.

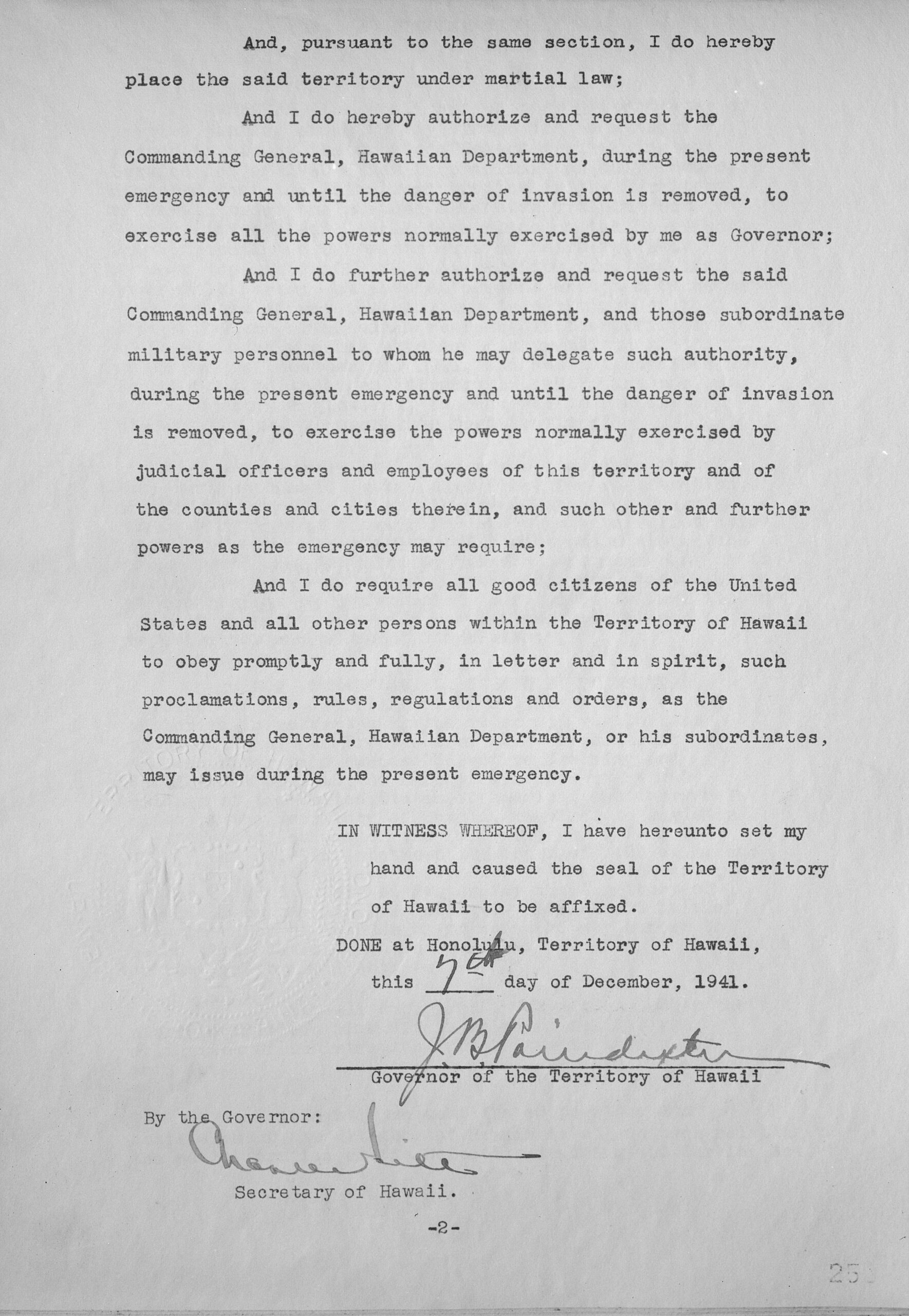

In 1863, a military court in Indiana sentenced Lambden Milligan to death for disloyal activities including an alleged plot to overthrow the state government. In Ex Parte Milligan (1866), however, a divided United States Supreme Court ruled that the president violated the Habeas Corpus Act of 1863 by ignoring the requirement of a grand jury indictment and that Congress lacked the authority to institute military courts to try civilians in areas remote from the actual fighting and where civil courts were open. “The Constitution,” the Court’s majority opinion stated, “is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times, and under all circumstances.” The majority, therefore, followed that “Martial law cannot arise from a threatened invasion. The necessity must be actual and present; the invasion real, such as effectually closes the courts and deposes the civil administration.”

The court unanimously agreed that Milligan should not have been deprived of his habeas corpus privilege. Four justices, however, disagreed with the majority opinion that Congress did not have the power to authorize military commissions in areas threatened by invasion or insurrection. For them, the threat of war or insurrection was sufficient to warrant martial law, and that it should be left to Congress to decide whether or not to employ it.