©2023 Solid Light, Inc.

TheJudiciary History Center is the United State's first history museum created for a state judicial branch. Since 1989, the Center has served as a bridge between Hawaii’s Judiciary and the public, welcoming over 50,000 visitors a year. Together we can reimagine the Judiciary History Center to honor our past, inform our present, and inspire our future.

Aliiolani Hale: Place of Power, Witness to History

Aliiolani Hale is the nexus of Hawaii’s unique legal heritage: capitol building of the Hawaiian Kingdom, site of the overthrow of the Monarchy, and home to the Supreme Court since 1874. In the 19th century, Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) adapted western jurisprudence with traditional Hawaiian values and customs. Through this collaboration, Hawaiian Moi (monarchs) established Hawaii as an internationally respected, sovereign nation. The unprecedented hybrid legal structures created by the Monarchy in the 19th century distinguished Hawaii from the rest of the world then, to this day.

The Judiciary History Center is intimately positioned to interpret and commemorate this legacy in our redesigned exhibits. Visitors will gain new perspectives of Hawaii’s history through changing legal systems and cultural values from the time of traditional Hawaiian Kapu to modern civics. Fresh narratives will educate and stimulate conversation about Hawaiians and settlers employing different methods and tools to influence society. Visitors will be inspired to connect with Hawaii’s civic story, acknowledging their own role and kuleana (responsibility) in the process.

Your generous contributions will help us fulfill an ambitious yet critical phase of this project: renovating our infrastructure in Aliiolani Hale—preserving this beloved landmark and nationally registered historic site, ensuring Aliiolani Hale and the Judiciary History Center remain valued community resources.

©2023 Solid Light, Inc.

He Maopopo Hou o ka Moolelo Pohihihi

New Telling of a Complex Story

New galleries will explore the origins and sophistication of the traditional Hawaiian Kapu system, progressive court operations of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the ebb and flow between native and malihini (foreign) power to this day.

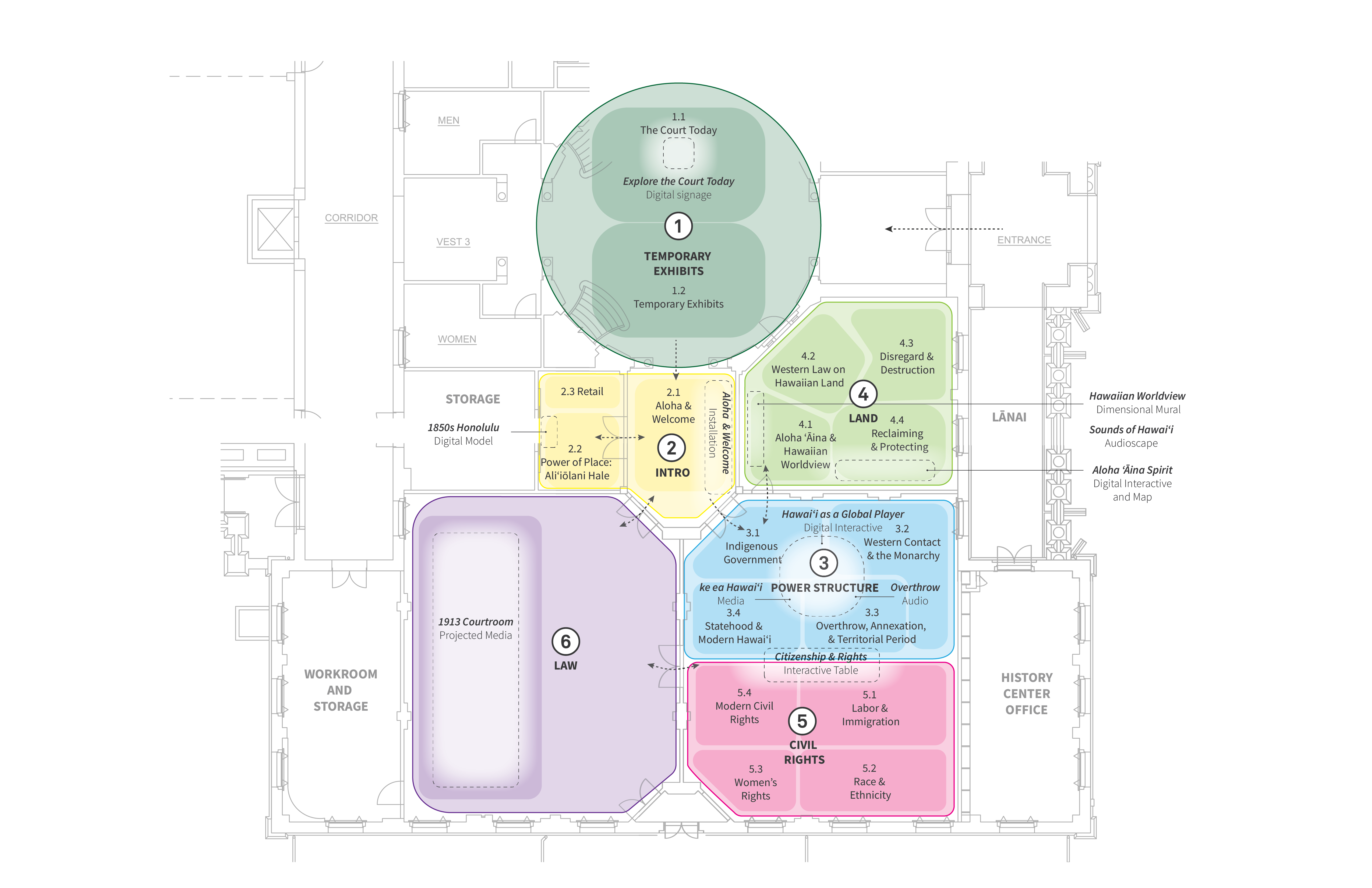

Interpretive spaces will be divided into thematic zones covering diverse topics outlined blow:

- Zones 1 & 2: Intro to Hawaii’s Legal Heritage and the Courts Today

- Zone 3: Power Structure under Hawaii’s Changing Governments

- Zone 4: Hawaiian Worldview, Land, Water, and Natural Resources

- Zone 5: Civil Rights and Citizenship Through the Centuries

- Zone 6: Oral Histories of Legislation, Public Policy, and Advocacy

Haina Ia Mai Ana ka Puana

Tension, Emotion, Empathy, and Understanding

We will share Hawaii’s civic story from the perspectives of Hawaiians and non-native settlers who made significant contributions to shaping society. The new galleries will provide an immersive visitor experience rooted in Hawaiian culture (olelo Hawaii, moolelo, oli, and mele). Historic photographs, paintings, courthouse objects, and primary-source documents will enrich the galleries and connect the public to Hawaii’s civic heritage, leaving lasting, memorable impressions.

Floorplans from the Friends’ “Exhibit Matrix” planning deliverable outline the intended placement of themes throughout the museum. ©2023 Solid Light, Inc.

Featured Stories

The following biographies provide snapshots into the lives of individuals who contributed greatly to the civic and legal development of Hawaii. These and other stories will be incorporated into the new galleries.

Miriam Auhea Kekauluohi’s life (1794-1845) spanned a period of significant change for the Kingdom, and she played a crucial role in shaping its political and social landscape.

Early Life and Marriages:

Kekauluohi was born into the royal family, her father being a half-brother of Kamehameha I and her mother a wife of Kamehameha I. This lineage granted her immense prestige and positioned her at the heart of Hawaiian power. She married three times, first to King Kamehameha I, the founder of the Kingdom of Hawaii who was also her step-father, then married his successor Kamehameha II, and finally Charles Kanaina, a high chief and confidant.

Social Influence and Political Power:

Kekauluohi held the prestigious title of Kuhina Nui of the Kingdom of Hawaii. In this role, she wielded considerable power, acting as the kings advisor and co-ruler. She was known for her intelligence, strategic thinking, and strong leadership. She was a patron of the arts, encouraging the development of Hawaiian music, dance, and language. She also practiced traditional medicine and was deeply respected for her knowledge and wisdom.

A member of the House of Nobles, Kekauluohi sat as a judge on the superior court of the Kingdom and played a key part in establishing the first Hawaiian constitution, co-signing it with Kamehameha III in 1840. The constitution incorporated the 1839 declaration of rights, which stated that the government was based on Christian values and equality for all people. The constitution defined the house of representatives as the legislative body for which people had the right to vote, created the office of royal governors for each island, and gave that house and the house of nobles the power to change the constitution. The western style of the constitution was intended to signify that the Kingdom was an independent sovereignty whose laws and authority should be respected by all. She had on several occasions had to negotiate with foreign powers to protect the Kingdom’s sovereignty. Her son was elected by the legislature as King Lunalilo of Hawaii in 1873 but enjoyed only a very brief reign before his death from tuberculosis.

Legacy:

Kekauluohi’s life and achievements stand as a testament to the power and influence of Hawaiian women. She was a skilled politician, a judge, a strong cultural advocate, and a loving mother to King Lunalilo. Her legacy continues to inspire generations of Hawaiians and serves as a reminder of the crucial role women played in shaping the nation’s history.

Iona Kapena (died March 12, 1868), was a prominent figure in the Kingdom of Hawaii during the 19th century. He served as a royal advisor, statesman, and judge.

Early Life and Education:

Born into a chiefly family, Iona Kapena received a traditional Hawaiian education, which included training in warfare, politics, and religion. He later attended Lahainaluna Seminary, graduating in 1835. At Lahainaluna, Kapena was exposed to people and concepts of governance that would shape his future political career. His classmates included historians, David Malo and Samuel Kamakau and politicians, Boaz Mahune and Timoteo Haalilio.

Political Career:

After graduating from Lahainaluna, Kapena became a trusted advisor to Kinau, the Kuhina Nuit. In this capacity, Kapena represented Kinau in the drafting of Hawaii’s first fully-written constitution, the Constitution of 1840. This document established a constitutional monarchy and guaranteed basic rights for its citizens of the Kingdom. It codified the political structure of the Kingdom as a constitutional monarchy, and also created the Supreme Court and legislature.

In addition to his role in the drafting of the constitution, Kapena served as a member of the House of Nobles, the upper house of the Hawaiian legislature. He also held the position of judge and later was elected by the legislature to be an assistant judge of the Supreme Court of Hawaii. He worked also as a newspaper editor for one of the Kingdom’s first Hawaiian language newspapers and for the paper that eventually became Ke Nupepa Kuokoa.

Throughout his career, Kapena advocated for the preservation of Hawaiian culture and traditions while simultaneously promoting modernization and progress.

Legacy:

Iona Kapena remains an important figure in Hawaiian history. He is remembered for his contributions to the development of the Kingdom of Hawaii and his efforts to preserve Hawaiian culture and traditions. His legacy continues to inspire future generations of Hawaiians who strive to build upon the foundation laid by their ancestors.

Born in Fukuoka, Japan in 1867, Yeiko Mizobe So left an indelible mark on women’s history in Hawai’i. Arriving in Honolulu in 1895, she quickly recognized the plight of Japanese women immigrants facing abuse and exploitation. Undeterred by the challenges, So dedicated her life to providing refuge and support to these women and to neglected children. She founded the Japanese Women’s Home as a shelter for ‘picture brides’ who were escaping abusive husbands. In 1905, she founded the Home for Neglected Children, adopting her daughter, Esther, from the shelter.

Early Life and Education:

Yeiko Mizobe So was born to a samurai family. Married and then widowed at the age of 21, she converted to Christianity after meeting the missionary couple from Hawaii, Orramel H. Gulick and Ann Gulick. She enrolled in the Kobe Women’s Seminary and graduated in April, 1893. At the seminary, Mizobe So and other students learned the value of making one’s own decisions in both the domestic and public spheres.

Establishing Safe Havens:

At the suggestion of the Gulicks, the Hawaii Board of Missions invited Mizobe So to serve as missionary to the growing Japanese immigrant community. She arrived in Honolulu on May 20, 1895. She toured the islands shortly after arriving, finding many of the arranged marriages common among the immigrant population to be far from the devoted partnership that the Gulicks enjoyed. In 1895, So established the Japanese Women’s Home on Alapai St. in Honolulu, a shelter offering safety and sanctuary to picture brides and their children fleeing their abusive marriages and social isolation on the sugar plantations. Operating from 1895 to 1905, and serving over 700 women,this pioneering initiative provided crucial support, including legal assistance, reproductive health education, and job training, empowering women to rebuild their lives. Drawing on her seminary education, Mizobe So also supervised the reception and treatment of picture brides at the Territorial Immigration Center. Many women were able to leave the Home and live independent lives. When the Immigration Center took over the Home’s functions, Mizobe So founded the Home for Neglected Children and served over 350 children from both rural plantations and urban areas before her retirement in 1931.

Breaking Barriers:

So’s work extended beyond the walls of the shelter. She actively challenged social norms and advocated for reforms to protect women’s rights. She campaigned against forced prostitution and pushed for legislative changes to address domestic violence. Her tireless efforts paved the way for greater equality and justice for Japanese women in Hawaii.

Born in 1862 in Japan, Katsu Goto arrived in Hawaii in 1885 as part of the first wave of government-sponsored Japanese contract laborers. Unlike most contract workers who toiled in the scorching sugarcane fields, Goto learned English before leaving Japan, as an employee of the Port of Yokohama. This knowledge allowed him to emerge as a bridge between the Japanese community and the plantation owners.

However, Goto’s story is not one of mere adaptation. He became a staunch advocate for the rights of his fellow laborers, facing the often brutal realities of plantation life head-on. His fluency in English made him a vital interpreter, ensuring fair wages and decent working conditions were understood by both sides.

When injustice arose, Goto was not one to remain silent. He challenged discriminatory practices, poor living conditions, and wage theft, becoming a thorn in the side of plantation management. He organized strikes, wrote letters to local newspapers, and even petitioned the Hawaiian government on behalf of the workers.

His activism, however, made him a target. Four years after arriving in Hawaii, a mob of white and Portuguese plantation workers, incited by rumors of a planned uprising, brutally lynched Goto in Honokaa. His death sent shockwaves through the Japanese community and sparked outrage across the islands. His murderers were tried and found guilty but either escaped or were pardoned by the new government of Hawaii and released from prison after only four years.

Though tragically short, Goto’s life left an indelible mark. He defied the stereotype of the meek plantation worker, proving that even amongst the sugarcane fields, voices for justice could rise. His sacrifice fueled the fight for labor rights and ethnic equality in Hawaii, inspiring future generations of activists and leaders.

Key aspects of Goto’s life and work:

- Interpreter and Mediator: Bridged the gap between Japanese laborers and plantation owners, ensuring communication and understanding.

- Labor Rights Advocate: Challenged unfair practices, low wages, and poor living conditions, becoming a voice for the voiceless.

- Community Organizer: Mobilized workers and raised awareness about the plight of Japanese laborers.

Ah Quon McElrath (1915-2008) was a titan of Hawaii’s labor reform movement, dedicating her life to fighting for fairness and equality for workers across the islands. Born Leong Yuk Quon in 1915 to immigrants from Zhongshan, China, she grew up witnessing the harsh realities faced by plantation and cannery workers and dockworkers. After her father’s death, she and her siblings worked in pineapple canneries. It

Early Activism and Education:

McElrath’s journey began on the bustling streets of Honolulu, where she honed her leadership skills while attending McKinley High School. She later enrolled in the University of Hawaii, becoming a vocal advocate for student rights and social justice while earning bachelor’s degrees in sociology and anthropology which were awarded in 1938. It was during this time that she embraced the name “Ah Quon,” signifying her connection to her Chinese heritage. She later helped to create the Ethnic Studies program at UH and served on its Board of Regents from 1995 to 2003.

Joining the Labor Movement:

The burgeoning labor movement in Hawaii provided Ah Quon with a platform to amplify the voices of the marginalized. She joined the leftist Interprofessional Association and later became a key figure in the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 142.

Fighting the “Big Five”:

Hawaii’s economy was dominated by the “Big Five” corporations – sugar plantations and other powerful conglomerates. Ah Quon McElrath tirelessly led strikes and campaigns demanding fair wages, better working conditions, and an end to discriminatory practices. Her unwavering commitment and strategic acumen earned her the respect and admiration of her fellow workers.

Retirement and Recognition:

McElrath retired in 1981, leaving behind a legacy of social and economic transformation. She received numerous awards and accolades, including the Order of Distinction from the State of Hawaii, recognizing her lifelong dedication to improving the lives of countless individuals.

Ah Quon McElrath’s impact on Hawaii remains profound. Her unwavering commitment to justice and equality continues to inspire generations of activists and workers fighting for a fairer future.

Haunani-Kay Trask (1949-2021) was a towering figure in the Hawaiian Sovereignty movement, a scholar, activist, poet, and author who dedicated her life to challenging the injustices faced by the Native Hawaiian people. Born in San Francisco and raised on the island of Oahu, Trask witnessed firsthand the devastating impact of colonialism on her homeland and its people. This fueled her lifelong passion for justice and advocacy for Hawaiian self-determination.

Trask’s intellectual journey began at Kamehameha Schools, followed by earning degrees in political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her academic pursuits were deeply intertwined with activism, as she embraced critical Indigenous studies and feminist theories to challenge the dominant narratives of Hawaiian history and identity.

Trask’s academic career flourished at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where she founded and directed the Kamakakuokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies. As a professor, she mentored generations of students, instilling in them a critical understanding of Hawaiian history and the ongoing struggle for sovereignty.

Beyond academia, Trask’s activism took many forms. She co-founded Ka Lahui Hawaii, a leading organization advocating for Hawaiian self-determination, and was a vocal critic of the United States’ role in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. She addressed audiences around the world, speaking out against injustices and advocating for the rights of Indigenous peoples everywhere.

Trask’s written works include her best-known book, “Notes From A Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaii Which was published in 1993 and influenced a generation of student activists and Native Hawaiian scholars. This was the same year that she led a march of Native Hawaiians to Iolani Palace to protest the 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the monarchy with rogue U.S. support. Her poems, woven with passion and anger, lamented the loss of sovereignty while celebrating the resilience of the Hawaiian spirit.

Haunani-Kay Trask’s legacy is a testament to the unwavering pursuit of justice. She challenged power structures, championed Indigenous rights, and inspired generations to fight for a brighter future for Hawaii. Her voice, though silenced in 2021, continues to resonate, urging us to confront the injustices of the past and work towards a future where Hawaiian sovereignty is finally recognized.

Key Aspects of Trask’s Life and Work:

- Scholar and Activist: Trask combined her academic expertise with activism, using her platform to challenge colonial narratives and advocate for Hawaiian sovereignty.

- Founder and Director of the Kamakakuokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies: Trask played a crucial role in establishing this important center for Hawaiian scholarship and activism.

- Co-founder of Ka Lahui Hawaii: This organization remains a leading voice in the Hawaiian sovereignty movement.

- Prolific Writer: Trask’s books and poems remain influential contributions to Indigenous studies and Hawaiian literature.

International Advocate: Trask addressed audiences around the world, raising awareness about the struggles of Indigenous peoples.

Born on December 28, 1853, in Charleston, South Carolina, to free Black parents, Thomas McCants Stewart rose to become a prominent figure in the late 19th century as a lawyer, civil rights leader, and minister. His life and work were marked by a relentless pursuit of justice and equality for African Americans.

Education and Early Activism:

Stewart’s early life was shaped by a strong sense of community and a thirst for knowledge. Despite limited educational opportunities for Black children in the post-Reconstruction South, he managed to attend private schools and even enrolled in the prestigious Lincoln University in Pennsylvania.

In 1877, Stewart continued his education at Princeton Theological Seminary, one of the first Black students admitted to the institution. While at Princeton, he actively participated in the civil rights movement, engaging in debates and advocating for racial equality.

Minister and Advocate:

After graduating from Princeton, Stewart became an ordained minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He served in various churches throughout the country, including prominent congregations in New York City. Beyond his religious duties, Stewart remained deeply committed to social justice.

He co-founded the Afro-American League in 1887, an organization dedicated to promoting the political, economic, and social advancement of African Americans. Stewart used his legal training and oratorical skills to fight against discrimination and advocate for equal rights in areas like voting, education, and employment.

Legal Pioneer:

In 1880, Stewart graduated from Columbia Law School, becoming one of the first Black lawyers in the United States. He established a successful law practice in New York City, representing clients in various cases related to racial discrimination and civil rights violations.

Thomas McCants Stewart relocated to Hawaii in 1898. He represented clients from diverse backgrounds, including Chinese immigrants facing exclusionary laws. Stewart also helped draft the Honolulu City Charter and advocated for Native Hawaiian rights, particularly in regaining their Kuleana lands. He later served as Associate Justice of the Liberian Supreme Court and settled in the Virgin Islands, where he passed away in 1923.

Legacy of Leadership:

Throughout his life, Thomas McCants Stewart remained a tireless advocate for African Americans. He embodied the spirit of the Reconstruction era, fighting for equal rights and opportunities despite the challenges of systemic racism and discrimination.

Stewart’s legacy extends beyond his legal and political contributions. He was also a writer, editor, and public speaker, using his platform to raise awareness about social injustices and inspire others to fight for a more just society.

Fred Kinzaburo Makino (1877-1953) was a newspaper publisher and pivotal figure in the history of Hawaii, leaving an indelible mark on the lives of Japanese immigrants and the fabric of society. An Issei born in Yokohama, Japan, he arrived in Hawaii in 1899 to assist his brother in a small store and to find work on a plantation. He had learned to speak English from his father who was a British trader but died when Makino was only four-years-old. He learned Japanese traditions and values from his mother who was from Kanagawa prefecture. He practiced law informally from an office above the Makino Drug Store in Honolulu. Makino’s journey, however, was destined for a far greater impact.

Dissatisfied with the existing Japanese-language newspaper, Makino founded the Hawaii Hochi in 1912. This became a powerful voice for the immigrant laboring community, advocating for their rights and challenging discrimination. Makino fearlessly tackled issues like labor disputes and unfair treatment, becoming a champion for the underdog. His unwavering commitment to justice earned him the respect and admiration of many.

Makino’s activism extended beyond the pages of his newspaper. He actively participated in community organizations, promoting cultural understanding and fostering collaboration between various ethnic groups. He was a staunch advocate for education, believing it to be the key to individual and collective advancement. His efforts helped pave the way for greater integration and acceptance of Japanese immigrants within Hawaiian society.

Despite his public advocacy of controversial positions on such issues as Japanese language schools, citizenship rights, and continued labor unrest, his support for the Japanese community never waived. The military government took over the Hawaii Hochi along with other Japanese language newspapers, but Makino was not incarcerated along with other prominent Japanese Americans during World War II. He continued to publish the Hawaii Hochi, albeit under government control. This controversial position sparked criticism, but Makino maintained that his primary goal was to serve the community and provide a voice for the voiceless.

After the war, Makino remained a leading figure in the Japanese-American community, promoting reconciliation and rebuilding trust. He remained active in public life until his passing in 1953, leaving a legacy of courage, resilience, and dedication to justice.

Today, Fred Kinzaburo Makino is remembered as a pioneer, a champion of human rights, and a true embodiment of the Aloha spirit. His unwavering commitment to equality and his tireless efforts on behalf of his community continue to inspire generations. He serves as a powerful reminder that one person, with unwavering conviction and a strong voice, can make a profound difference in the lives of many.

Harriet Anne Bouslog (née Williams, later known as Harriet Bouslog Sawyer or Harriet Sawyer; 1912-1998) was a pioneering labor lawyer who dedicated her career to defending the rights of workers in Hawaii. She navigated a rapidly changing social and political landscape, challenging power structures and advocating for fair treatment for all, especially plantation and waterfront workers of all ethnicities who were marginalized and disenfranchised.

Early Life and Education:

Born in 1912 in Maxville, Florida, Bouslog moved to Indiana with her family at a young age. She excelled academically and pursued a bachelors of law degree at the University of Indiana Bloomington, graduating in 1936. This was a remarkable achievement for a woman at the time, paving the way for future generations of female lawyers. She moved to Honolulu in 1939 with her husband who had obtained a teaching position at the University of Hawaii. They both left for jobs in Washington, D.C. after martial law, declared in December, 1941, made her legal practice impossible. The provost courts handed out harsher penalties to defendants who were represented by legal counsel.

Work with the National War Labor Board:

In Washington, D.C., Bouslog worked for the National War Labor Board. This experience exposed her to the struggles of workers and the importance of collective bargaining in securing fair wages and working conditions.

A Champion for Hawaiian Workers and Unions:

After the war, Bouslog returned to Honolulu to defend sugar workers facing criminal charges following the 1946 strike. She quickly became a prominent figure in the local labor movement, using her legal skills and unwavering commitment to justice to advocate for the rights of Hawaiian workers. Bouslog faced significant challenges in a male-dominated field and a society with ingrained prejudices against women and labor unions. Her outspoken defense of union members charged with seditious conspiracy during the McCarthy era led to her suspension from legal practice by the Territory of Hawaii Supreme Court. She had explained to a rally of ILWU members that a fair trial was impossible in criminal cases under the Smith Act of 1940. She challenged her license suspension all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1959 that lawyers have First Amendment rights to criticize the prosecution’s arguments in cases they are defending. Her license to practice law in Hawaii was reinstated.

Daniel Ken Inouye (September 7, 1924 – December 17, 2012) was an American politician who served as a United States Senator from Hawaii from 1963 to his death in 2012. He was the first Japanese American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, and he was the third-highest-ranking official in the U.S. government at the time of his death.

Early Life and Military Service:

Inouye was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, to Japanese immigrants. He attended McKinley High School, where he excelled academically and athletically. After graduating, he enlisted in the U.S. Army to fight in World War II. He served with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese American unit that fought with great distinction in Europe. Inouye was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism in rescuing fellow soldiers during a fierce battle in Italy.

Political Career:

After the war, Inouye graduated from the University of Hawaii and George Washington University Law School. He entered politics in the 1950s, serving in the Territorial House of Representatives and the Territorial Senate. In 1959, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, becoming the first Japanese American to serve in Congress.

In 1962, Inouye was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he served for 50 years. He was a powerful and influential figure in the Senate, and he served on many important committees, including the Appropriations Committee, the Commerce Committee, and the Foreign Relations Committee. In 1965, senators Hiriam Fong and D.K. Inouye championed the ‘Pacific State’ proposal. This was an idea to incorporate the former Trust Territories of the Pacific into the State of Hawaii. This would have added more than two thousand islands to Hawaii’s jurisdiction, islands that today are the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia. Inouye played important roles in the highly-visible hearings of the Watergate Committee and the investigation of the Iran-Contra, arms-for-hostage scandal during the Reagan administration. As the President pro tempore of the Senate from 2010 to 2012, Inouye was the third-highest ranking official in the U.S. government at the time of his death.

Legacy:

Inouye was a respected and admired figure in Hawaii and across the United States. He was a strong advocate for the rights of veterans, minorities, and the people of Hawaii. He was also a tireless supporter of education and the arts. Inouye’s legacy is one of public service, courage, and commitment to justice.

Born in 1808, alii Timoteo was a key figure in the history of the Kingdom of Hawaii. A member of the House of Nobles established under the 1840 Constitution, he served as a royal secretary and diplomat, and was pivotal in securing recognition by foreign powers of the Kingdom’s independence and in promoting its progress.

Haalilio was born into a prominent family on the island of Oahu and was entrusted to the care of King Kamehameha III at a young age. This allowed him access to a quality education, including instruction in English and Hawaiian languages, as well as mathematics and composition. He excelled in his studies, demonstrating a sharp intellect and a strong work ethic.

In 1839, Kamehameha III appointed Haalilio as his personal secretary. This position placed Haalilio at the heart of the Hawaiian government, and he quickly proved himself to be a skilled administrator and trusted advisor. He was entrusted with managing the King’s finances and overseeing the construction of important government buildings, libraries, and hospitals. Hawaiian historian Noenoe Silva writes that he was one of the king’s most trusted advisors, and he was sent abroad to forestall colonization by one of the great powers that were then actively adding Pacific island kingdoms to their empires.

In 1842, he embarked on a critical fourteen-month diplomatic mission around the world. Accompanied by American missionary William Richards, his goal was to secure official recognition of Hawaiian independence from major powers like the United States, Great Britain, and France. The mission was a resounding success. Haalilio’s impressive diplomatic skills, combined with the support of Richards and the changing geopolitical landscape, paved the way for international recognition of Hawaii as a sovereign nation.

Tragically, Haalilio’s life was cut short at the age of 36. On the return voyage from his diplomatic mission, he passed away on December 3, 1844, leaving behind a legacy of service, dedication, and achievement.

Boaz Mahune (died March 1847) was a 19th-century Hawaiian teacher, royal secretary, judge and civil servant who helped shape the Kingdom of Hawaii’s political landscape. He is best known for being the author of the first draft of He Olelo Hoakaka, or the Declaration of Rights of 1839, which served as the foundation for the Kingdom’s first constitution.

Little is known about Mahune’s early life, including his exact birth date and place. However, historical records suggest that he was born into a family of lesser Hawaiian nobility and was a member of the first class of the Lahainaluna Seminary, a prestigious institution established by American missionaries in 1831. He studied under the school’s first principal, Lorrin Andrews. His classmates included future historian David Malo, future royal advisor Jonah Kapena, and future diplomat Timoteo Haalilio. Graduating in 1835, he was selected to remain at the school to assist in translations and teach in the children’s school.

Contribution to the 1840 Constitution and Hawaiian law:

In 1839, King Kamehameha III sought to modernize the Kingdom’s government and establish a constitutional monarchy in order to increase the Kingdom’s visibility to foreign powers. A group of young Hawaiian intellectuals, including Mahune, were tasked with drafting a constitution. Mahune took the lead in crafting the document’s preamble, known as the He Olelo Hoakaka, influenced by the U.S. Declaration of Independence which he had studied at Lahainaluna.

Following the adoption of the 1840 Constitution, which incorporated the declaration of rights, Mahune served in various government positions. He was appointed as a judge in Lahaina and later became a member of the Privy Council. He also held the position of Minister of the Interior from 1842 to 1845. He also wrote many law codes including the laws concerning taxation.

Born in 1842 on the Big Island of Hawaii, Joseph Nawahi (also known by his full name Iosepa Kahooluhi Nawahiokalaniopuu) emerged as a multifaceted figure during a tumultuous period in Hawaiian history. He was a lawyer, politician, journalist, painter, and most importantly, a staunch advocate for the rights and sovereignty of the Hawaiian people.

Born near Hilo, Hawaii in 1854, Emma Nawahi was of half-Native Hawaiian and half-Chinese descent. Her father was a Chinese sugar planter on lands leased from King Kamehameha V. She grew into a staunch opponent of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its annexation to the United States. She later was a supporter of women’s suffrage and a founder of the Democratic Party in Hawaii.

Educated at Hilo Boarding School, Lahainaluna, and the Royal School, all run by American missionaries, Joseph Nawahi’s early life was nevertheless steeped in Hawaiian traditions and culture. However, as American influence grew, he witnessed the erosion of Hawaiian autonomy and the injustices faced by his people. He became a self-taught lawyer and surveyor, fields from which he readily entered politics.

Nawahi served in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s House of Representatives from 1872 to 1892, advocating for land rights, Hawaiian language education, and greater autonomy from the United States. He even founded the newspaper “Ka Nupepa Kuokoa” (“The Independent Newspaper”) to voice Hawaiian perspectives and challenge the growing American influence. He was a prolific painter, capturing scenes of Hawaiian life and landscapes in vibrant colors, often imbued with symbolic messages of resistance and resilience.

Nawahi’s unwavering commitment to his people’s cause was evident during the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy. He vehemently opposed the annexation of Hawaii by the United States and actively defended the rights of Queen Liliuokalani, helping her to draft the ill-fated 1893 Constitution to restore the monarchy. He petitioned the U.S. Congress and even traveled to Washington D.C. to plead for Hawaiian sovereignty, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. After his involvement with the unsuccessful Wilcox Rebellion, Nawahi was arrested for treason and jailed in Oahu Prison, where he likely contracted tuberculosis. Following his release, he and his wife Emma Nawahi established a weekly anti-annexation newspaper, Ke Aloha Aina, written in Hawaiian, which she continued to publish until 1920.

Despite the many setbacks, the Nawahi’s continued to fight for Hawaii’s independence. They founded men’s and women’s chapters of Ka Hui Hawaii Aloha Aina (The Hawaiian Patriotic League) to oppose the annexation treaty. In 1897, Emma’s branch, Ka Hui Hawaii Aloha Aina o Na Wahine, gathered over 21,000 signatures of Hawaiian island residents who opposed US annexation. Her correspondence with Liliuokalani during this period also preserved a record of the Queen’s tireless efforts on behalf of her nation.

Shigeo Yoshida (1907–86), an educator and civic leader, played a central role during World War II among Nisei in preventing the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans in Hawaii and also in maximizing Japanese American participation in the war effort.

He was a community leader during the war, integrally involved in organizing the Varsity Victory Volunteers labor battalion, the Army’s deployment of the Japanese American 100th Battalion, and mobilizing the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. His liaison work with the martial law government helped convince the Army officers not to engage in mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans in Hawaii. His civic engagement helped to prepare the Japanese community to live as equal citizens in the postwar period.

Early Life and Education:

A passion for learning and leadership marked Yoshida’s upbringing. Born and raised in Hilo, Hawaii, his parents had immigrated as a couple, allowing Yoshida as an early Nisei to acquire an education and develop cross-cultural leadership skills decades before the onset of World War II. A talented debater, he attended the University of Hawaii and became friends with the founding chairman of the UH Board of Regents, Charles Reed Hemenway, and with Hung Wai Ching, who, as secretary of the Chinese American YMCA would later serve with Yoshida on interracial unity during the war period. He used his university education to become a classroom teacher and school principal as well as a civic leader.

World War II and the Home Front:

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the declaration of martial law, Shigeo Yoshida worked with a multiethnic group of civic and military leaders to promote racial unity and to mobilize the Japanese community to contribute to the war effort. Their work through the Morale section of the Office of Civil Defense and later the military governor was an important liaison to the various communities and helped to dampen anti-Japanese animosity in the face of constant rumors of disloyalty and the capricious prosecutions and racial profiling of the martial law provost courts. As Tom Coffman has written, the community’s show of strength, its interracial institutions and the high quality of its leadership was fueled in part by agreement of the value of American democracy. These forces which Yoshida and his colleagues nurtured allowed Hawaii to emerge from the war period a more just and equitable society.

William Shaw Richardson (December 22, 1919–June 21, 2010) was a prominent figure in Hawaiian history, serving as a lawyer, politician, and Chief Justice of Hawaii State Supreme Court from 1966 to 1982. He is remembered for his unwavering commitment to justice, and his landmark decisions that vindicated Native Hawaiian values and rights to access and use sustainably the lands, waters and oceans of Hawaii nei.

Early Life and Education:

Chief Justice Richardson was born in 1919 in Honolulu of European and Hawaiian (Alapai-nui) ancestry on his father’s side and Chinese ancestry on his mother’s side. As Carol Dodd has written “a more appropriate lineage could not be invented for a true son of the islands.” His grandfather was a leading supporter of Queen Liliuokalani and opponent to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Richardson referred to himself as “just a local boy from Hawaii.” He was a graduate of Roosevelt High School, University of Hawaii at Manoa, and University of Cincinnati College of Law. Richardson served in World War II with the 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment as a platoon leader with a rank of Captain in the U.S. Army. After the war he returned to Hawaii and continued his military service in the Judge Advocate General Corps.

Political and Legal Career:

Richardson entered politics in the 1950s, serving in the Territorial House of Representatives and the

Territorial Senate. He was known for his progressive views and his dedication to improving the lives of Hawaiians. In 1966, he was appointed Chief Justice of the Hawaii State Supreme Court, becoming the first chief justice of Hawaiian ancestry since the time of Kamehameha III.

Landmark Decisions and Legacy:

As Chief Justice, Richardson authored several landmark decisions that recognized the unique legal and cultural history of Hawaii. He championed the rights of Native Hawaiians, protected the environment, and promoted public access to beaches and natural resources.

Richardson’s legacy extends beyond his legal career. He was a staunch advocate for Hawaiian culture and sovereignty. He supported the Hawaiian language revival movement and played a key role in the renovation and restoration of Aliiolani Hale and establishing the William S. Richardson School of Law.

Antone Rosa was a lawyer and royalist politician in the period of change in Hawaii from kingdom to republic and then to U.S. territory. He held many offices during the reign of King David Kalakaua including that of attorney general, private secretary, and as vice chamberlain and major of the royal household. He served also on the Privy Council to Queen Liliuokalani and was her staunch supporter during the political crisis preceding her overthrow in January 1893. Rosa was given numerous medals and awards for his loyal service. In 2020, Rosa family descendants donated these important artifacts of the royal period for display at Iolani Palace.

Early Life and Education:

Rosa was born at Kalae, Molokai on Nov. 10, 1855. His mother was Native Hawaiian. His father, Antone Rosa, Sr., was a fisherman from the Azores islands in Portugal and arrived in Hawaii on a whaleship in 1850. Scholars consider Antone Rosa, Sr., born about 1826 and arrived in 1852, to typify the early, pre-1878 group of Portuguese immigrants who settled in Hawaii after working in the fur and sandalwood trades and on whaling ships.

His eldest son, Antone Rosa was educated at the Roman Catholic College of ʻĀhuimanu and later Honolulu’s Royal School under Anglican Rev. Alexander Mackintosh, Rosa became fluent in English, Hawaiian and French. He received his legal education through a clerkship under Chief Justice Charles Coffin Harris, and served as Deputy Clerk of the Supreme Court from October 25, 1877, to September 3, 1882. In order to qualify to practice as an attorney, he took a two-year sabbatical to study law, and passed the bar exam on October 27, 1884.

Career:

Rosa was serving as deputy attorney-general in 1885 when King Kalākaua appointed him Attorney-General on November 15 to fill a vacancy caused by the departure of John Lot Kaulukou. As Attorney General, Rosa was a member of the king’s cabinet, a high-profile position that associated him with the very unpopular administration of Walter Murray Gibson. He held that position until June 1887, when the cabinet was ousted in events preceding King Kalakaua’s forced signing of the constitution of 1887. The so-called ‘Bayonet Constitution’ reduced the executive powers of the king, restored and increased the property and wealth qualifications of voters for the legislature, and denied suffrage to Asian subjects of Asian descent and to those unable to meet wealth and literacy thresholds.

Rosa was a member of the Hale Naua Society, a fraternal organization founded to foster native Hawaiian leaders in government and public service and refounded by Kalakaua to promote the arts and sciences. Rosa was nominated to run as an Independent candidate for representative from Honolulu in 1887, but he was defeated by the Missionary/Reform Party candidate. In October 1887, Kalākaua appointed him as his private secretary and Vice Chamberlain of the Royal Household, where he held the rank of Major. He also served as acting commander-in-chief and adjutant general of the forces of the Kingdom, and acting governor of Oahu. In the February 1890 general election, Rosa won a seat in the legislative assembly in which Rosa and his fellow legislators ousted the Reform cabinet led by Lorrin A. Thurston, author of the bayonet constitution.

After the death of Kalakaua, Rosa was appointed in March, 1891 by Queen Liliuokalani to her Privy Council of State. During the political crisis prior to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Rosa supported the queen. He and other royalist leaders formed the Committee of Law and Order, an unsuccessful counter to the Committee of Safety which insisted upon the queen’s abdication and declared a provisional government which could engineer the annexation of the kingdom as a territory of the United States, to which export duties would not attach.

When a circuit court judge died suddenly in 1896, Rosa was appointed as his replacement under the Republic of Hawaii. He eventually resigned the judgeship and returned to private practice. He defended native Hawaiians in criminal cases including two co-defendants in the last capital murder case tried in the Kingdom, in 1897. Kapea Kaahea was convicted of killing Dr. Jared Smith, a doctor who had ordered that his sister be removed to the leprosy colony on Molokai.

Rosa died on September 9, 1898, at his residence in Pawaa, Honolulu, after a lengthy illness. The funeral was held on the same day at the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace officiated by Bishop Gulstan Ropert, and he was buried at the Honolulu Catholic Cemetery.

Born in 1847 to a high-ranking Hawaiian chiefess and an American sugar planter, Emma Kailikapuolono Metcalf Beckley Nakuina was a woman who defied societal boundaries and carved her own path in Hawaiian history. Her life, spanning six monarchs and five governments, was a testament to her courage, intellect, and unwavering dedication to her people.

Born and raised in Manoa, Nakuina’s upbringing instilled in her a deep respect for both Hawaiian traditions and Western education. She attended Sacred Hearts Academy and Punahou School in Honolulu and was privately tutored in many languages by her father. King Kamehameha IV ordered that she be trained in traditional water rights and customs. This unique blend of knowledge became her foundation for a remarkable career.

Nakuina’s accomplishments were diverse and impactful. She served as:

- Curator of Hawaii’s first National Museum: During King Kalakaua’s reign, Nakuina oversaw the Hawaiian National Museum, located in Aliiolani Hale. She significantly expanding its collection and established herself as an authority on Hawaiian history and culture. In this role, it is believed that she traveled with then-Princess Lydia Liliuokalani to Nihoa island, the first of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, to visit sacred sites and collect ancient cultural artifacts.

- Cultural Writer and Historian: She authored several books and articles, preserving Hawaiian traditions and knowledge for future generations. Her work included “Hawaii: Its People and Their Legends” and “Ancient Hawaiian Water Rights,” both seminal contributions to Hawaiian cultural understanding.

- Water Commissioner: Nakuina’s keen understanding of Hawaiian water rights led her to serve as a water commissioner, ensuring equitable access to this vital resource for her people. In this role, Nakuina defied gender norms by becoming one of the first female judges in Hawaii.

- Women’s Suffrage Advocate: Nakuina played a pivotal role in the fight for women’s suffrage in Hawaii. After the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, she and other women tirelessly campaigned for voting rights, which were finally granted in 1920.

Nakuina’s life was not without challenges. She navigated a complex political landscape, faced societal prejudices against women and Native Hawaiians, and witnessed the devastating impact of colonialism on her people. Yet, she persevered, her unwavering spirit and dedication to her community leaving an indelible mark on Hawaiian history.

Garner Anthony (1899-1982) was a prominent business lawyer and civic leader who played a pivotal role in Hawaii’s legal history during the turbulent 20th century.

Early Life and Legal Career:

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he attended the Quaker school, Swarthmore College and then Harvard Law School. While still in high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as a field artillery officer in World War I.

Upon graduation from law school, he moved to Honolulu in the 1920s and established a successful legal practice representing the Big Five sugar industry conglomerates. He served as president of the Hawaii Bar Association. In 1942, he accepted the appointment as territorial attorney general by Governor Stainback, in order to challenge the military regime under martial law, which he had analyzed in an important law review article, concluding that the Organic Act, the law by which Hawaii became a U.S. territory did not authorize the governor to turn all government functions and judicial process to the military. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. military imposed martial law in Hawai’i, severely curtailing civil liberties and leading to discriminatory practices against Japanese Americans. Anthony emerged as a vocal critic of these measures, arguing for the restoration of constitutional rights and the protection of all citizens, regardless of ethnicity. He resigned his position of attorney general in order to challenge in federal court the legality of convictions of civilians by the military courts. In 1946, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with his argument that all provost court convictions of civilians during martial law were illegal.

After the war, Anthony won at trial the controversial case of United States v. Fullard-Leo, defeating the US Navy’s claim of title to the remote atoll of Palmyra, which the U.S. had occupied as a naval base during the war. He also successfully represented the Bishop and Damon estates and the Robinsons of Niihau in land title and water disputes.

Anthony was elected as a delegate to the 1950 Hawai’i Constitutional Convention, where he helped draft the state’s constitution. In 1958, he was appointed to the Hawaii Statehood Commission and in 1962 to the committee that drafted the modern rules of civil procedure. His commitment to fair process and justice ensured that the constitution and laws of the state protected the rights of all Hawaiians.

Pablo Manlapit (1891-1970) was a fiery advocate for Filipino workers in the sugar plantations of Hawaii. Born in the Philippines, he arrived in Hawaii in 1910, joining countless others seeking a better life. Yet, the reality was far from idyllic. Filipino laborers faced harsh conditions, low wages, and discrimination from plantation owners.

Early Activism and the Rise of the Filipino Labor Union:

After leaving the plantation and moving to Honolulu with his young family, he studied law and published a local Filipino newspaper. Manlapit quickly recognized the injustices faced by his fellow Filipinos and became a vocal critic. He helped establish the Filipino Labor Union (FLU) in 1921, becoming a key figure in advocating for better working conditions and challenging discriminatory practices.

The Hanapepe Massacre and its Aftermath:

In September 1924, the Hanapepe Massacre erupted, a violent clash between striking workers and police that resulted in the deaths of 16 strikers and 4 policemen. Though not present, Manlapit was falsely accused of inciting the violence. He was arrested, convicted of conspiracy, and sentenced to 2-10 years at Oahu prison.

Deportation and Continued Activism:

Fearing his influence, authorities deported Manlapit to the mainland U.S. upon his release.

Undeterred, he continued his activism in California, organizing Filipino workers and fighting for their rights. He co-founded the United Filipino Labor Union and became a prominent voice for Filipino Americans in the United States. He returned to Hawaii in 1933 but was promptly deported to the Philippines where worked again in politics and labor organizing.

Legacy of Resistance and Inspiration:

Manlapit’s story is a testament to the resilience and courage of Filipino laborers in Hawaii. He fought tirelessly against exploitation and discrimination, even in the face of persecution. His legacy continues to inspire activists and labor leaders who fight for justice and equality for all workers.

Patsy Matsu Takemoto Mink (1927-2002) was a towering figure in American politics and a champion for gender equality and social justice. From humble beginnings in Hawaii to the halls of Congress, Mink dedicated her life to breaking barriers and paving the way for a more equitable society.

Early Life and Activism:

Born in Paia, Hawaii, in 1927, although she was chosen valedictorian and elected student body president at Maui High School, Mink witnessed firsthand the limitations placed on women and minorities. This spurred her passion for social justice, leading her to become active in student and community organizations while attending law school at the University of Chicago.

Breaking Barriers in Law and Politics:

In 1951, Mink became the first woman of color to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School. She returned to Hawaii and established a successful legal practice, focusing on civil rights and women’s issues. In 1959, she made history again as the first woman and first person of color elected to the Hawaii House of Representatives.

A Champion for Equity in Congress:

In 1964, Mink made the leap to national politics, becoming the first Asian American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She served six consecutive terms, during which she became a powerful advocate for a wide range of issues, including:

- Education: Mink authored Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, a landmark law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded education programs. This had a profound impact on women’s access to sports, athletics, and educational opportunities.

- Civil Rights: Mink fought for racial equality and championed the rights of minorities, immigrants, and refugees.

- Women’s Rights: She was a vocal advocate for women’s reproductive rights and pay equity, and tirelessly challenged gender stereotypes and discrimination.

Beyond Congress:

After leaving Congress in 1977, Mink continued to serve the public, holding positions at the U.S. Department of State and Honolulu City Council. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter named Mink as assistant secretary of state for oceans and international, environmental, and scientific affairs in 1977. In this position she was called on to resolve the bowhead whale question that threatened to derail the federal government’s international conservation efforts on behalf of whales or violate its trust responsibilities to Native Alaskan whaling villages.

She returned to the House of Representatives in 1990 and served until her death in 2002. Throughout her career, she received numerous accolades for her dedication to social justice, including the posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009.

Legacy of Inspiration:

Patsy Mink’s legacy is one of groundbreaking achievements and relentless pursuit of equality. She paved the way for generations of women and minorities in politics and law, and her unwavering commitment to social justice continues to inspire activists and politicians across the globe.

Key Aspects of Mink’s Life and Work:

- First woman of color to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School

- First Asian American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

- Authored Title IX, a landmark law prohibiting sex discrimination in education

- Championed civil rights, women’s rights, and equality for all

- Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her contributions to society

George Jarrett Helm Jr. (March 23, 1950 – disappeared March 7, 1977) was a Native Hawaiian activist, musician, and cultural icon from Kalamaula, Molokai. He remains a revered figure in Hawaiian history, remembered for his passionate advocacy for Kanaloa (the Island of Kahoolawe), Hawaiian sovereignty, and cultural preservation.

Early Life and Activism:

Born and raised on Molokai, Helm embraced his Hawaiian heritage from a young age. He was deeply inspired by the natural beauty of Kahoolawe and the traditions of his ancestors. In the 1970s, as the U.S. Navy intensified its bombing practices on the island, Helm emerged as a leading voice against the desecration of sacred land.

He co-founded the Protect Kahoolawe Ohana in 1976, becoming its president and a powerful spokesperson for the movement. Helm’s charisma, eloquence, and deep understanding of Hawaiian culture resonated with people across the islands, garnering widespread support for the cause. The Ohana filed a civil lawsuit against the Navy for continued bombing of the island and surrounding waters, invoking the federal environmental laws the U.S. Congress had enacted in the early 1970s. After his disappearance, the Ohana was led by Emmett Aluli and Davianna McGregor. Native historian and musician, Jonathan K. Osorio writes that Helm’s address to the Hawaii House of Representatives, three weeks before his disappearance, was critical to the eventual agreement to end the bombing, restore the island’s environment, and transfer title to the State of Hawaii in trust for Kanaka Maoli.

Music and Cultural Preservation:

Beyond his activism, Helm was a talented musician and songwriter. His music, infused with traditional Hawaiian styles and contemporary rock influences, became anthems for the Kahoolawe movement. Songs like “Kahoolawe” and “Ua Mau ke Ea o ka Aina” captured the anger, sorrow, and unwavering determination of the Hawaiian people in their fight for their sacred island.

Helm also recognized the importance of preserving Hawaiian language and traditions. He actively participated in cultural revival efforts, advocating for the teaching of olelo Hawaii (Hawaiian language) and encouraging the practice of traditional chants, dances, and rituals.

Tragic Disappearance and Legacy:

In 1977, at the age of 26, Helm mysteriously disappeared at sea while sailing from Molokai to Oahu with his friend and cousin, Kimo Mitchell. Their bodies were never found, adding to the tragedy and fueling speculation about their fate.

Despite the circumstances of his disappearance, Helm’s legacy continues to inspire generations of Hawaiians. He is remembered as a fearless advocate for Kahoolawe, a gifted musician who gave voice to the island’s spirit, and a passionate defender of Hawaiian culture.

Impact and Recognition:

- The Hawaiian community continues to honor Helm’s memory through music festivals, cultural events, and educational programs.

- His music remains a powerful symbol of the Kahoolawe movement and a source of inspiration for Hawaiian activists and artists.

- In 2017, Helm was posthumously awarded the prestigious Na Mele o Hawaii Lifetime Achievement Award for his contributions to Hawaiian music and culture.

George Helm’s story reminds us of the power of individual voices in the fight for justice and cultural preservation. His legacy continues to guide the Hawaiian community in their ongoing efforts to protect their land, language, and traditions.

Sanji Abe was a pivotal figure in Hawaiian history, becoming the first Japanese American elected to the Territory of Hawai’i’s Senate in 1940. Born in 1895 in Kailua-Kona on the Big Island, he lived during a time of significant change and challenges for Japanese Americans in Hawai’i.

Early Life and Education:

Abe’s parents, Matsujiro and Raku, immigrated to Hawai’i from Japan in 1893, joining the ranks of contract laborers who helped fuel the islands’ sugar industry. Despite facing discrimination and limited opportunities, Abe pursued his education, graduating from Hilo High School in 1915. He became a prominent businessman and civic leader, operating a popular movie theater in Hilo and organizing local sports. He notably took a baseball team to Japan in 1921.

Military Service and Public Service:

Abe’s patriotism and dedication to his community were evident in his enlistment in the Hawai’i

National Guard. Although drafted during World War I he continued to serve the Honolulu Police Department as a Japanese interpreter, rising to the rank of assistant chief of police This role allowed him to bridge the gap between the immigrant community and the local authorities.

Political Career:

Driven by a desire to improve the lives of his fellow Japanese Americans and contribute to the larger Hawaiian society, Abe embarked on a political career. A member of the Republican Party, in 1938, he was elected to the Territorial House of Representatives, where he advocated for education, labor rights, and social justice.

In 1940, Abe made history by becoming the first person of Japanese ancestry elected to the Territorial Senate. This groundbreaking achievement paved the way for greater political representation for Japanese Americans in Hawai’i. Abe’s political career was cut short by the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II in Hawaii. He was suspected of having loyalty to the empire of Japan when, at a hearing before a board of officers and civilians, his cultural and sports exchanges with Japan were used as evidence against him. He was incarcerated in the camp at Honouliuli and forced to resign his Senate seat in February, 1942. According to historian Kelli Nakamura, Abe lost his seat due to a purge of loyal American office holders of Japanese ancestry. He was eventually paroled and then released from custody in February, 1945. He returned to his Hilo business importing and promoting Japanese movies, but his theater was destroyed in the 1960 tsunami.

Legacy and Impact:

Despite these hardships, his legacy as a trailblazer and champion for his community endures. He demonstrated the power of political participation and paved the way for future generations of Japanese-American leaders in Hawai’i.

We look forward to working with our community to perpetuate history made, past and present, at Aliiolani Hale. We hope you will join us in this endeavor to tell our shared civic story.

The King Kamehameha V Judiciary History Center’s museum redesign is made possible by funding to the Friends of the Judiciary History Center of Hawaii, from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.